A River and Its Water: Reclaiming the Commons - Part 17

17th in a Series

The Monster Frack

He did the frack, he did the monster frack,

The monster frack, drilled like a maniac.

He did the frack and made himself some jack.

He did the frack. . . until the earth did crack.

Apologies to Bobby “Boris” Pickett & The Crypt Kickers (click here and sing along)

In “Uncharted Waters,” The New York Times’ meticulous and eye-opening investigative series on the threats to the nation’s groundwater, I was introduced to “the monster frack” – enormous hydraulic fracturing operations that have “transformed the global energy landscape, turning America into the world’s largest oil and gas producer, surpassing Saudi Arabia.” (For those of us who lived through the “oil crisis” years of the 1970s, this is an incredible sentence to read.)

Extracting massive amounts of fossil fuels from deep under the ground costs a lot of money. It also requires a lot of water – millions of gallons for each new well, according to the Times’ research. Across the country, fracking has used almost 1.5 trillion (that’s 11 zeros after the 5) gallons since 2011. The industry claims that much of the water it uses is either brackish or recycled. Let’s hope so, but their water use is mostly unregulated, unpermitted, and unmonitored.

Moreover, unlike stream and river water, which is owned by the public, in many places the water in aquifers is owned outright by the landowner. “In Texas,” said Bill Martin, rancher and water conservation district member, “if you own the surface, you own everything to the center of the earth.” Perhaps a Chinese farmer owns from the center out the other way.

Anyway, since you own it, you can sell it, and in parts of Texas landowners pump as much water on their property as they like, even if it’s coming from under someone else’s land. And “if you’ve got water to sell,” Bruce Frasier, an onion farmer who sells groundwater to a fracking company, told the Times, “you’re making a fortune.”

That water is coming from the same vulnerable aquifers that everyone else is trying to tap into – water that has been in the ground for thousands of years and which replenishes itself very slowly. And it isn’t only an issue in the West.

“Most of the water we’re pulling out of the ground is thousands of years old,” Jason Groth, deputy director of planning and growth management in Charles County, Maryland, told the Times. “It’s not like it rains on Monday, and by Saturday it’s in the aquifer.” He predicts that, with the massive growth in suburban Washington, D.C. draining its aqueducts, the county won’t have enough water in ten years.

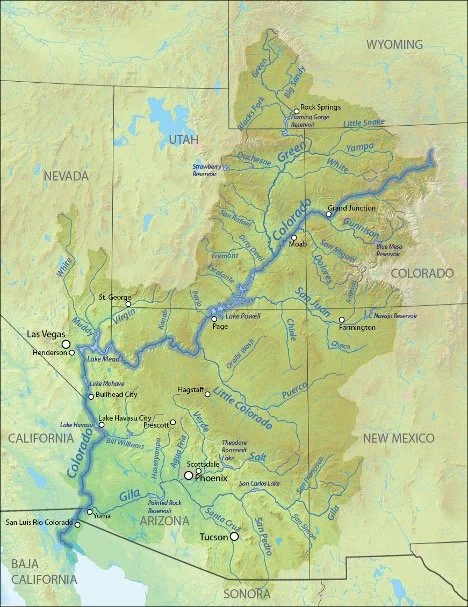

When you start thinking about water as little more than drinkable oil, the next step is to drill massively for it and send it through pipelines to places that are willing to pay for it. Actually, that has been going on for years. Right now, an Israeli company has proposed a $5-billion project to build a desalination plant near the Sea of Cortez in Mexico and pump the “fresh” water 200 miles to Phoenix. The city of Sonora will also get some much-needed fresh water and Mexico some money. The Sea of Cortez will get the industrial waste.

To see all of this and earlier series, please go to https://jamesgblaine.com