Pretty Baby

“I, the Lord your God, am a jealous God, punishing the children for the sin of the parents to the third and fourth generation . . . .“ Book of Exodus (20:5)

Hessy Levinsons Taft died on New Years day at her home in San Francisco. She was 91. Born in Berlin in 1934, she had come to New York City with her family in 1949. After graduating from Barnard College in 1955, she entered the PhD program in chemistry at Columbia University. There she met her future husband, a distinguished mathematician named Earl Taft. They both taught at Rutgers until Hessy left academia to raise their two children. Years later she joined the faculty at St. John’s University, where her research focused on water sustainability. I had never heard of Hessy Taft before, and all my information comes from her obituary and from Wikipedia.

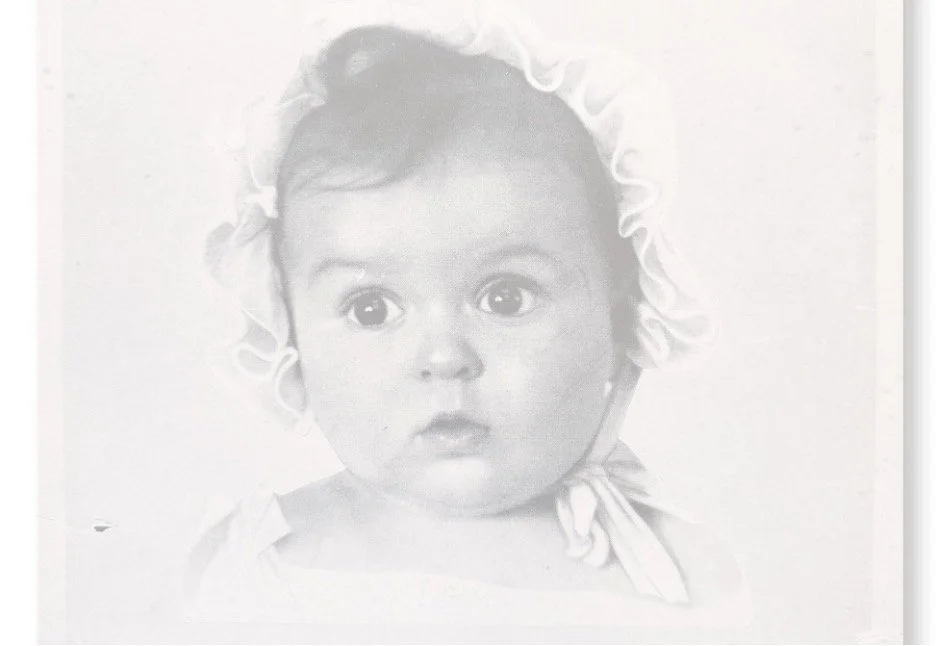

Dr. Taft’s life is remembered, not for her academic or familial accomplishments, however, but for a photograph taken of her when she was six months old by a well-known photographer named Hans Ballin. Ballin entered that photo, along with several others, into a contest to find Germany’s “most beautiful Aryan baby.” This was a big deal: Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi government’s Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, was the contest’s judge. Goebbels pronounced Hessy’s photo the winner. What followed was a whirlwind of images of the baby all across the country: in advertisements, on postcards, and on the cover of “Sonne ins Haus” (“Sun in the Home”), a pro-Nazi magazine and one of the few periodicals to have survived Hitler’s press shutdown.

This was, to say the least, ironic. Hessy Levinsons was Jewish.

The closest modern-day equivalent I can think of would be if Stephen Miller anointed, as the cutest baby of the new American empire, a child of Venezuelan immigrants.

Winning the contest was more than ironic. It was dangerous. Hetty’s parents were Latvian-born Jews who had emigrated to Berlin in the late 1920s to pursue their careers as opera singers in what was then the artistic capital of Europe. When the cleaning woman brought them a copy of the magazine cover, they were scared for their lives. “I can laugh about it now,” Hessy said 80 years later, “but if the Nazis had known who I really was, I wouldn’t be alive.”

The odds of Hessy winning the contest were below infinitesimal. First of all, it’s safe to assume she was the only Jewish entry. Second, the Nazis were obsessed with race and eugenics, and they produced enormous amounts of “scientific” research – from measuring ideal facial characteristics and coding eye color to ensuring that no drop of impure blood went undetected – to demonstrate their own racial superiority and to prove that others, especially Jews, were subhuman. (Such efforts were also pursued in Jim Crow America and apartheid South Africa.)

There are two morals to Hetty’s story. The first is that all babies are beautiful, especially to their parents. That’s why politicians kiss them. The second is that, if the most beautiful Aryan baby – chosen by Joseph Goebbels himself, no less – is a Jew, isn’t it time to put all the rancid theories of racial purity and ethnic inferiority in the dung heap where they belong?

Stephen Miller appears to disagree. His target is immigrants, particularly those from “third world countries” – and not just those who are undocumented or newly arrived, but those whose families have lived here for generations.

“With a lot of these immigrant groups, not only is the first generation unsuccessful. Again, Somalia is a clear example here,” he said on Fox News, “You see persistent issues in every (italics mine) subsequent generation. So you see consistent high rates of welfare use, consistent high rates of criminal activity, consistent failures to assimilate.”

Goebbels would be pleased.